At 15,000+ words, this tome is one of the most ambitious projects we have ever undertaken at the Opioid Data Lab. We hope you'll read the whole thing, but in a series of posts, each linked at the bottom of this post, we pull out the most important points in non-technical language. First let's take a look at the why and who and how we did this work.

Why we needed to learn more

We start by acknowledging that overdose reversal record keeping requirements from funders can be a considerable impediment to actual service delivery. Data on how many doses were handed out and how many reversals reported often end up as vanity metrics. We felt the data could have a lot more value if we worked with the program and activists to contextualize.

Surprisingly, there is limited published documentation of how harm reduction programs adapt to changing drug supplies, laws, pharmaceutical formulations, and societal norms over an extended time. We know this happens, it's part of the work. And we have limited understanding of how peer reversal behaviors change over time, particularly as the drug supply landscape has evolved.

What we learned

Doses of naloxone needed

Many scientists have pointed out that increasingly high doses of naloxone may not be necessary to reverse fentanyl overdoses in the community setting. We sought to objectively capture if the number of doses needed for survival had changed over 17.5 years.

Impact of state legislation

We were interested in seeing how state legislation changed naloxone provision and overdose response. Pennsylvania Act 139 was enacted on November 30, 2014, and went into affect the immediately following January.

Titration to avoid adverse events

We also wanted to bring attention to the practice of naloxone titration with injectable naloxone. People who use drugs will often use partial doses of naloxone, monitor for return to breathing, and administer doses more slowly to avoid putting people into withdrawal. This is the first paper to document the positive benefits of titrating naloxone doses by people who use drugs to prevent withdrawal.

Here are a few of our other blog posts from the paper. Please let us know if you want to see other pieces as posts (opioiddatalab@unc.edu).

- About naloxone

- Brief history of community naloxone distribution

- Evidence making interventions

- Programs have powerful underutilized data

- Long-term changes in types of naloxone distributed

- Have naloxone doses gone up with fentanyl?

- Do people use naloxone on themselves?

The Setting

Prevention Point Pittsburgh is one of the longest continuously operating overdose prevention programs in the world. The overdose prevention program is helmed by the redoubtable Alice Bell. She created the overdose prevention program, conducted thousands of the interviews, and still runs the service two decades later. Malcom Visnich handles a sizable portion of the day to day operations on the mobile van, and would often call in to our meetings from on-site.

Prevention Point Pittsburgh has published other important papers using their data here, here, here, and here. They have been using a consistent data collection form to record overdose response events (OREs) when their participants came back for naloxone refills. They were an ideal research-ready partner.

A letter of love

It was Louise Vincent who said "Love is a research value."

The way in which we did the science was also infused with respect, an emphatic THANK YOU to all the Prevention Point staff and volunteers over 2 decades who have spent their weekends doing life giving work, the compassionate care, providing basic human needs, when nobody else would. They do this work out of love for their community, and it was incumbent upon us to honor the thousands of hours of work that gave rise to the data, and do so out of love.

National Perspective

The authors come from three professional domains: harm reduction program staff, government and academic scientists, and public health advocates. Our approach to generalizability wasn't to extrapolate one program's experience to all of harm reduction. Instead, our approach was to position the experience in Pittsburgh within a national perspective. We relied on 💜 Eliza Wheeler and 💜 Maya Doe-Simkins from Remedy Alliance/For The People, two naloxone pioneers and living heroes, who each have decades of experiences doing direct service, advocacy, technical assistance, and bulk naloxone distribution. Their longview and broadview was instrumental in deducing how what we observed in Pittsburgh connected with what was happening at the hundreds of programs that Remedy serves.

Government Scientists

Finally, we have deep respect for our colleagues at the US Food and Drug Administration. Led by Jana McAninch, the co-authors came from 4 different departments within the Agency, bringing depth of regulatory, clinical, and scientific perspectives. The rest of the co-author team were Amy Seitz, Dorothy Chang, Summer Barlow, and Zach Dezman. In addition, the working group included a dozen other FDA officials. We've had a longstanding collaboration with Jana and her team(s), and have always found them to be scientifically rigorous and open-minded partners. Thank you for helping us uncover and document the real story behind community naloxone distribution!

Dream Team

Combing all these folks together was Adams Sibley and Maryalice Nocera at UNC. We also want to thank the reviewers who read the manuscript with an incredible eye to detail, despite the incredible length. We don't know who you are, but your contributions were immensely helpful!

Conceptual Framework

🙈 Did your eyes just glaze over? Bring 'em back! This is important.

A powerful aspect of this work was applying the Evidence Making Intervention (EMI) framework, by Kari Lancaster and Tim Rhodes. The EMI framework shifts the locus of evidence production away from universally generalizable knowledge, which is common in traditional biomedical research. (And what narrowly defines NIH's funding mission.)

Instead, EMI prioritizes a more contextualized scientific process in which data and conclusions are generated through localized public health interventions serving immediate, applied needs. Therefore, the purpose of this analysis is not to present the hypothetically universal experience of naloxone distribution, but rather to examine one location in-depth to understand the forces that directly impacted service delivery and naloxone utilization.

We unpack the jargon at the start of the Methods section, but in summary these were the main core values:

- The most important thing was that PPPGH was providing life-saving prevention services; data were useful but secondary to the mission.

- We each have different ways of knowing that are equally valid, whether we are formally trained scientists, program staff, government regulators, or activists.

- It's critical to understand how programs and participants adapt to local circumstances.

We relied on EMI because we were faced with two difficult questions:

How can we analyze 17.5 years of data with fidelity, knowing that drugs and circumstances were constantly evolving?

Here's our answer: By listening to the people who were there and did the hard work of caregiving.

How do we create equality between programmatic experience and quantitative data?

Here's our answer: In the final paper, after each quantitative variable reported, we present a dedicated section called "Programmatic Context," which reflects co-authors AB’s and MV’s lived experience from years of direct service delivery, program coordination, and employee supervision. During full team meetings, relevant programmatic context for each variable in the dataset was discussed, and recorded in meeting notes. Following the EMI principles of Equality of Knowledge and Practice Implementation, these conversations often took the shape of program staff and advocates (MDS and EW) informing scientists and government officials about the nuance of service delivery.

Put another way, honoring programmatic context and lived experience turned away from a nerdy exercise, and instead it became a space for mutual learning. In addition to a better scientific end product, we emphasize that the process induced by the EMI framework was genuinely enjoyable. The back-and-forth between people of different backgrounds revealed much more than any one party could have contributed by themselves.

👉🏾 Read out blog post on EMI here.

Methods

We encourage you to look at the Methods in detail. In brief:

Data Collection & Analysis

We analyzed naloxone distribution records spanning nearly 18 years (2005-2023), tracking when people received naloxone kits and later reported using them during overdoses. Data were collected on standardized forms by trained interviewers, with ongoing quality assessments. We combined quantitative data with programmatic insights from staff who directly delivered services, ensuring our analysis reflected real-world harm reduction practice.

Key Measurements

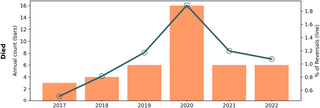

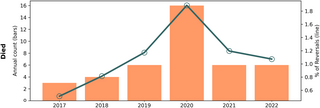

We measured how many doses were needed per overdose and tracked side effects like withdrawal symptoms ("felt sick"). We created novel surveillance metrics to understand naloxone usage patterns, predict future needs, and detect overdose surges in the community. These metrics showed strong agreement with hospital emergency department overdose trends, validating their utility for public health monitoring. We also examined how participant demographics changed over the study period.

Statistical Analysis

We examined trends across three drug epidemic phases: prescription opioids/heroin (2005-2011), heroin dominance (2012-2015), and fentanyl era (2016-2023). We used segmented regression, a statistical technique that identifies sudden changes in trends over time, particularly useful for evaluating the impact of the 2014 Pennsylvania law enabling broader naloxone distribution, including effectiveness and usage patterns. Time series visualizations with smoothed trend lines helped illustrate changes over the 210-month study period.

Death Case Review

We compared effectiveness between different naloxone formulations and conducted detailed reviews of 23 cases where people died despite naloxone administration, examining circumstances and timing.

Open Science Principles

Because this was a federally funded study, and because we wanted anybody to be able to use the results, we followed Open Science best practices. While we've adhered to parts of the Open Science framework in other studies, it's taken a lot of trail-and-error to learn how to implement. It's so worth it!

- We pre-registered the study, announcing our intent and planned analyses before we started. This makes us accountable to our original plan. In the final paper we also noted ways in which we deviated from what we had said we would do.

- We made our methods and code publicly available, using Stata and Jupyter notebooks.

- We posted the data with permission of Prevention Point Pittsburgh.

- We paid Prevention Point for their data and time on the project. And they are co-authors.

- We posted versions of our paper so people could see how our how the science evolved, and to inform a broader audience during peer review, but we consciously didn't publicize the pre-print.

- We presented the results at the Compassionate Overdose Response Summit (video, slides) while the paper was going through a year-long review process because we felt the information couldn't wait.

- We published the paper in an open access journal "free of all copyright, and may be freely reproduced, distributed, transmitted, modified, built upon, or otherwise used by anyone for any lawful purpose." Slides for each figure are pre-made for your at the link.

Doing all the things took intentional effort. And time. We hope we can live up to this standard in all our work, but we know that not all projects can make all this happen.

Research Questions

Five research questions were specified in the public pre-registration. If you're looking for the answers, this section of the published paper evaluates each question.

- Did the utilization rate of naloxone and demographics of participants change after enabling state legislation was enacted?

- After enactment of state legislation, what actions did the program take to focus uptake of naloxone directly to networks of people who use drugs?

- Were program adaptations (e.g., site expansion) effective in improving naloxone uptake among communities of color in Pittsburgh?

- Has the average number of doses of naloxone administered during an overdose response event changed over time as the drug supply has changed? Specifically, was more naloxone needed for reversing overdoses during the era of illicitly manufactured fentanyl, compared to previous periods where overdoses were due to heroin?

- Is the number of doses administered per overdose response event impacted by type of naloxone formulation?

Three additional questions were developed by the co-authors during the iterative analysis process and evaluated in accordance with the Evidence-Making Intervention (EMI) framework.

- Did enactment of the Pennsylvania “Good Samaritan” law impact the proportion of overdoses response events in which 911 was called?

- What were the circumstances of deaths reported after administration of naloxone?

- Did adverse events differ by formulation of naloxone? And did titration of naloxone have an impact on adverse event rates?

The answers to all 8 questions are clearly stated in the Discussion section that you can go to directly from this link:

Link to Discussion section