Most conversations about overdose reversals focus on someone stepping in to save another person’s life. But buried in our newly published analysis of 5,521 overdose reversal events (OREs) is a phenomenon that rarely receives attention: people giving naloxone to themselves.

This seems unlikely, right? If some is in a true "overdose" situation, they are by definition unresponsive. This is also technically off-label, because these naloxone formulations are supposed to be used in opioid-induced respiratory depression.

Why would someone use naloxone right after using heroin or fentanyl, when it would just be wasting money, and possibly put them into withdrawal?

Sometimes there may be a short window when people realize they took something that feels stronger than they expected. Injectable naloxone can be given in less than a full dose, meaning people may choose a small amount of antidote to prevent themselves from going into a full overdose. This likely happens when people use drugs alone. We recommend our friends at Safe Spot (call 1-800-972-0590) if you need someone to spot you over the phone.

Look, we aren't endorsing that folks should give themselves naloxone. It would be easy to make yourself really sick. But, it's something that happens, albeit very rarely, and we figured we should look into it. In our study on 17.5 years of naloxone administration in Pittsburgh, we found some n=44 cases where people reported self-administering naloxone.

How common is self-administration?

In our dataset, 0.8% of all overdose reversals involved self-administration of naloxone (44 out of 5,521 overdose response events). That may seem small, but every one of these instances represents a moment when someone recognized quickly enough—and had naloxone close enough—to act before losing consciousness.

Most of the time, people who reversed their own overdoses used injectable naloxone (77.3%, or 34 of 44 instances). And in the majority of cases, they gave themselves one (or less) or two doses:

- 1 (or less) dose: 50% (22 events)

- 2 doses: 36.4% (16 events)

A chain of events

Here's approximately what happens in the sequence that leads to self-administration:

- Immediate perception of potency – Feeling the strength of the opioid agonist more quickly or more intensely than expected.

- Naloxone within reach – Having naloxone on hand and knowing how to use it. We've heard of folks pre-filling syringes with naloxone.

- Conscious recognition of overdose risk – People knew they consumed more than intended, or the drug was stronger than expected.

- Intervention before severe symptoms – They administered naloxone before respiratory depression or loss of consciousness.

Why did self-administration decline in the fentanyl era?

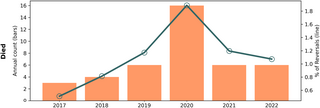

One of the striking findings is that self-administration used to be more common during the heroin and Rx opioid era.

- During the heroin and prescription opioid era (2005–2016): 14.4 self-administrations per 1,000 overdose response events

- During the illicit fentanyl era (2016–2023): 5.5 self-administrations per 1,000 overdose response events

That’s a three-fold drop.

Why the change? Likely because fentanyl’s onset is simply too fast.

With heroin or prescription opioids, people had enough time to realize, “This is too strong—I took too much.” With fentanyl, the window between “something feels wrong” and “I can no longer act” is dramatically shorter. Fewer opportunities for self-administration doesn’t mean less awareness; it means less time.

This highlights a cruel reality of the unregulated fentanyl supply: it compresses the timeline for life-saving action, even among people who know their bodies, who have naloxone ready, and who fully intend to use it.

Why this matters

Self-administration is a reminder that people who use drugs are not passive recipients of risk. They constantly make assessments, take precautions, and try to keep themselves—and others—alive.

What we don't know

Since this is such a rare phenomenon, there is a lot we don't know about it. How did people decide to use naloxone that particular time? Did people use less than a full dose? Did they inject it intramuscularly or intravenously? How did they decide on how much naloxone to give themselves? Was this something they did more than once? What happened once they had the naloxone? Why did they think they needed a second dose? Would they have used SafeSpot? Did they seek someone out to keep an eye on them in case they slipped back? Did they feel like using again because of the naloxone?

These are somewhat difficult questions, but things that are worth considering.

A final thought

You don’t hear much about self-administration of naloxone, but it represents a kind of self-defense—people doing everything they can in a rapidly changing risk environment. As fentanyl reshapes the timeline of overdose, these moments of quick thinking become harder to achieve.

We used generative AI tools to help generate some of the text for this post. We reviewed every word and edited substantially as we thought appropriate.